Excerpt from the winter 2022 issue of The Extension

Excerpt from the winter 2022 issue of The Extension

Paying for higher education in the United States has always presented a problem for some students and their families. Harvard established a loan program in 1840. The federal government began to play a larger role in assisting families and students in paying for higher education after World War II. One of the earliest federal programs was the GI Bill passed in 1944 to encourage returning soldiers to attend college. The National Defense Education Act followed in 1958. As a country, it seemed important for us to stay ahead of the rest of the world (especially the Russians) particularly in science and technology.

In 1965, the Guaranteed Student Loan Program was introduced as part of the Higher Education Act. No doubt, this legislation helped the nascent Wright State University. The Basic Educational Opportunity Act, better known as the Pell Grant, came into being. In 1992, FAFSA, the Free Application For Federal Student Aid, appeared along with Stafford Loans.

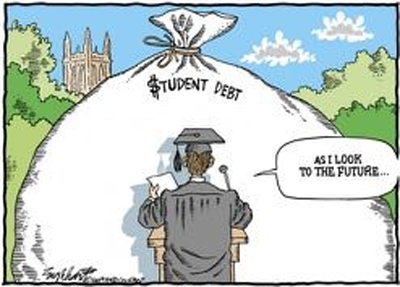

Outstanding student debt currently exceeds $1.7 trillion, more than national credit card debt. More than 44 million students took out loans averaging approximately $29,000 each. Over half of the students who graduated in 2019 had some level of debt. As of late 2020 most of that debt is not actually being repaid. Delinquent loans, defined as overdue by more than 90 days, comprise 6.5 percent of the total. Other groups have deferments ($114.4 billion), or forbearance ($887.4 billion), or are in a grace period ($43.7 billion). Repayment accounted for 4 million people and $14.7 billion. A shocking 3.2 million Americans owe $100,000 or more in student loans or $580.3 billion of the total.

Clearly, student debt is a huge financial problem for millions of Americans and it’s also a political hot potato. It’s easy to get lost in the data. It is important to remember that all the numbers come down to individual students. I recall a conversation I had with a student maybe 15 years ago. She had a dorm room but was commuting to classes from home because she had roommate problems. I urged her to try to resolve the roommate issues, pointing out that she was paying dearly for the room. She indignantly informed me that SHE wasn’t paying; it was part of her financial aid package. She represents for me the many, many 17- or 18-year-old students for whom the whole financial aid process is perhaps more complicated than they can grasp. Most of the borrowers are not old enough to rent a car or a hotel room, yet they sign on for what may turn out to be a lifetime debt. After all, college is the key to a good job and a good life.

Unfortunately, even for those who graduate and get a good job, the debt can be a drag on the rest of their lives. Many put off having children or buying a home until the debt is paid off. Much of the outstanding debt will never be repaid because the recipients did not graduate and literally do not have the means to make any payments. Others were lured into predatory training programs and borderline bogus schools. Think Trump University. Some of those loans have been forgiven, but not all. Currently, borrowers are enjoying an extended payment pause from the Biden administration until at least May of 2022. Many think that is not enough. Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and many other elected Democrats advocate canceling all student debt. Journalist Katrina vanden Heuvel says such a move would be “as strategically smart as it is morally urgent.” President Biden is hesitant, worrying about the optics of paying off loans for those who went to Harvard or Yale, but “fewer than 1 percent of borrowers attended an Ivy League college,” reports Annie Nova for CNBC. Biden is being urged to act before the midterms, because failing to do so may hurt Democratic prospects. Perhaps his frustration with other stalled legislation will prompt him to issue an executive order to fulfill the campaign promise he made to “forgive all undergraduate tuition-related federal student debt from two- and four-year public colleges and universities and private (historically Black colleges and universities) and (minority serving institutions) for debt holders up to $125,000.”

Note that only tuition-related debt would be forgiven. Former Wright State President David Hopkins often argued that tuition (even ever rising tuition) was not the problem. The real problem, he said, with student-loan debt was that they borrowed money for living expenses. It was in his interest to minimize tuition as part of a larger problem: higher education was becoming unaffordable for many Americans. When I attended Wright State in the 1970s, I was able to pay for tuition and books out of savings from the job I quit to go to college full-time. Tuition was, I believe, $240 per quarter. I don’t remember it going up during the time I was an undergrad. When I started work in the Honors Program in 1976, the $1,000 Honors Scholarships we awarded were enough to pay tuition and buy, at least, some books. By the time I retired in 2010, tuition was $2,599 per quarter, or $7,797 per per year. Add $1,800 for books and supplies, and students needed 10 times what they did in 1976 just to stay even.

I graduated without any student loan debt. I think the same is true for most other people in my age group. Even my working-class parents were able to send my sister to an out-of-state college in the 1960s. Of course, she worked during the summers and contributed what she could. Realizing that his parents could not afford much, my husband took a year off between high school and college and saved his money. Along with odd jobs during the school year and summer wages, he managed to complete a degree with no debt. We all have our stories. We were lucky to live in a time when public colleges and universities and even many private schools offered a first-rate education to working class students at a cost that left us debt free. That is why as a taxpayer I favor freeing the millennial generation from their student-loan burden. It is the right, the morally urgent thing to do.

Note: David Rathmanner compiled and posted the statistics used in this article on June 2, 2021.